Meadow Mix

Many people strive to plant a meadow from a can. Unfortunately, this is not at all easy or quick. Natural meadows can take centuries to become established.

We have a wonderful array of meadows around Jackson Hole not only because we have the right ecological conditions, but also because many places escaped grazing by sheep and cows. Fortunately, you can go enjoy a meadow without having to plant, water, and weed.

Meadows don’t come easily from a can but they can be easy to go see. In early July, we can see meadows beginning to bloom around Jackson Hole. The road to Two Ocean Lake, up Shadow Mountain, the hike to Ski Lake, and the trails south of Teton Pass to Mt. Elly all are relatively accessible, and as they vary in elevation, they keep blooming over the month.

Mountain meadows are also called “tall forb communities”. They are found where there is sun, moisture, and not too hot. Snow is deep and melts off late. Soils are relatively rich, deep, and often churned by pocket gophers.

Plants are similar to the perennials in a well-nourished and watered garden border: tall and lush. It is impressive to see how much biomass is produced each year from bare ground—plants are often 3-4’ tall by mid-July.

Meadows are rich habitats. Plants sustain myriad insects: caterpillars who eat the leaves before transforming into moths or butterflies. Lepidoptera along with bees, beetles, and flies of all sorts serve as pollinators. Pocket gophers, Uinta ground squirrels, as well as bears eat the roots; and pika, moose, elk, and deer browse on the stalks and flowers. Birds rely on the nutritious insects and seeds. Looking close with a 10x hand lens shows all sorts of tiny insects crawling around.

The following plants are the mainstays of our mountain meadows. Each meadow has its own combination, but the following species are typically part of the mix soon or later.

The truly tall meadow forbs:

Fernleaf Lovage – Ligusticum filicinum – is outstanding with its lacy skirt of very finely divided compound leaves and umbellate (remember umbrella) inflorescences of many tiny white flowers.

Fernleaf Lousewort – Pedicularis bracteosa – has erect 2-3′ stems full of yellow “irregular” flowers. Below the flower stalks are fern-like leaves, but not nearly as fine as the lovage above.

These flowers have co-evolved with different species of bumblebees who trigger the complicated apparatus of fused petals, hidden anthers, and single pistil to effect precise pollination. Bumblebees receive both pollen and nectar from this species. Fernleaf Lousewort is fading in lower regions but flourishing in higher meadows.

The species is hemiparasites on the Arrow-leaf Lousewort which also intermingles in moist meadows (see below) and Engelmann spruce where it receives sugars but also the alkaloid pinnidol. Nature has all sorts of relationships seen and unseen.

Giant Lousewort – Pedicularis procera – are not nearly as common as Fernleaf Louseworts and come out a bit later. As they name indicates, plants are much more robust growing to 4+’ and have reddish flowers with a definite long bract beneath.

I have seen them along trails at Munger Mountain, Brian Flat, and Game Creek

Mountain Bluebells – Mertensia ciliata – are dangling 2-4’ along mountain seeps and brooks. Their bluish green leaves have little stiff hairs along the edges: ciliate. Flower buds are pink, and open and turn blue when ready for various pollinators. The tubular petals fall off soon afterwards.

Jessica’s Stickseed – Hackelia micrantha – competes with Mountain Bluebells in capturing the the blue of the summer sky, and indeed they can be growing in the same vicinity, as in the bowls above Ski Lake.

The barbed fruits quickly form, ready to be carried along the trail by your dog or your socks.

Five-nerved Little Sunflowers – Helianthella quinquenervis – grow to about 4 up to 5’ in height. They appear to stare straight at you with their 3-4”-wide composite flowers.

Their lower leaves have five strong veins: the central vein, and two on each side.

One-flowered Little Sunflowers – Helianthella uniflora – can form colonies up slopes and across meadows. They are smaller in stature than their five-nerved cousin and have smaller flowers. The lower leaves have about 3 faint veins.

Silvery Lupines – Lupinus argenteus – are common in high elevations and as well as in shade at lower elevations. Compared to Silky Lupines – L. sericeous – which often grow with sagebrush on drier sunny slopes, Silvery Lupines overall are less hairy, flowers are a bit smaller and tighter, and the back of the banner (the upper petal) is typically smooth. (For the avid botanist there are 4 local varieties of Silvery Lupines). And for all lupines, the leaves are palmately divided: leaflets coming out from the center like the fingers from your palm.

In the Pea or formerly Legume Family, lupines all produce pods with seeds inside, like your common pea; but lupine pods and seeds are much tougher and the plant is poisonous with alkaloids. Plants “fix” their own nitrogen with the help of bacteria that reside in root nodules. The bacteria take the plentiful nitrogen (N2) out of the air (soil has air spaces) and convert it to a form usable by the plant: ammonium (NH4) which can be directly used to form proteins. (Clovers, vetches, etc. can do the same thing.)

Furthermore, lupines can be a host plant for paintbrushes (see below) which siphon off the alkaloids which then help protect paintbrush flowers from hungry insects.

Mountain Mint – Agastache urticifolia – is clearly in the Mint Family. The stems are square, the leaves opposite, and the pinkish flowers are bilateral – the flowers have two sides to them like your face, with several anthers sticking out. The final ID feature is that plant leaves, stems, and flowers are very fragrant. Hummingbirds, attracted by the pink bracts, hover to lap nectar, thereby pollinating Mountain Mints.

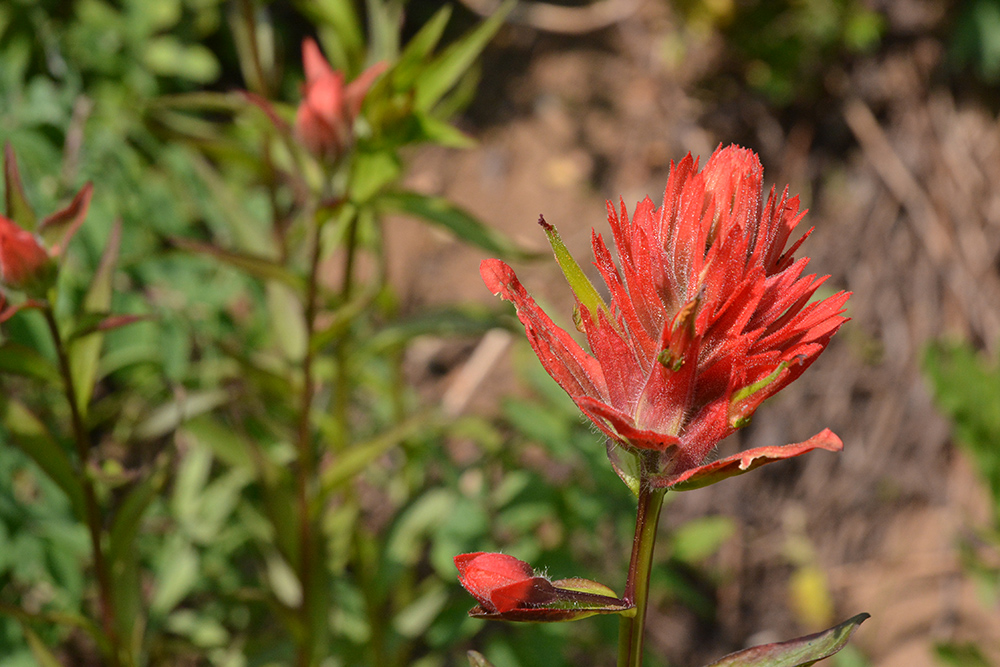

Sulphur Paintbrush – Castilleja sulphurea – can range in color from an orange to salmon to yellow to cream. They hybridize with red paintbrushes or muddle their chromosome numbers through polyploidy to make ID difficult. They are hemi-parasitic on a variety of meadow species.

Red Paintbrushes – Castilleja miniata – are frequent at lower elevations under aspens, forest edges, and grassy slopes. They can be up to a foot or more and often branch. They often hybridize with Pale Paintbrush (C. pallescens), if nearby. Their bracts and calyx lobes are sharply pointed.

Rosy Paintbrush – Castilleja rhexifolia – is found at higher elevations than Red Paintbrush They too can hybridize and have a range of colors. Compared to Red Paintbrush, Rosy paintbrushes are more upright and rarely branched. Bracts are 1-3-lobed with the center lobe widest and often rounded, as are the other lobes. The calyx lobes are also rounded. As I say they can be tough to tell apart for paintbrushes.

Tall Western Larkspurs – Delphinium occidentale – look like they belong in an English garden, they are so tall (to 6’) and dignified.

Studies have found that yeast passed along by bees can ferment the sugar in nectar and make flowers more attractive for pollination. Most parts of larkspurs are poisonous.

Monkshood – Aconitum columbianum – are also beginning to bloom mid-July in moist meadows and along streams. Their flowers are complicated with sepals forming the blue hooded framework over two stiff, arched nectaries which draw the insects inside.

Just below a mop of anthers forms first, and later they fizzle and the 3 female stigmas protrude. You can see this if you look at the flowers closely. Note all parts of Aconitum are poisonous.

In a study of a different species in Europe Aconitum napellus, scientists discovered that during those few days when the male anthers are fresh, plants exude more fragrance and more nectar to appeal to roaming bees. As it is not beneficial to the plant if the bee eats the pollen, the pollen is slightly poisonous. The bee is rewarded by nectar but deterred from feeding on the plentiful pollen. In any case, the bee flies to another flower where the three female stigmas are now standing out waiting. When the bee covered with pollen goes for another sip of nectar up under the hood, the pollen sticks to the protruding stigmas and pollination is affected.

Cow Parsnip – Heracleum spondylium var. lanatum – is the largest member of the Parsley Family – truly Herculean in stature – here in Teton County, growing up to 5 feet with broad compound leaves that can be 3’ across. The flowers welcome all sorts of insects, some who pollinate, some who just chow down on pollen and nectar. The hairs on the 1”-thick stems can cause a rash for those who brush against them, but not nearly as bad a reaction of blisters if you brushed against Giant Hog Peanut, an invasive taking over parts of the East.

Lyall’s Angelica – Angelica arguta – are equal in stature but not in heft to its cousin Cow Parsnip. Its white umbels are beginning to bloom now and attract all sorts of pollinators.

Angelica is more typical of shady forests, but also is found in seeps in more open sites. The compound leaves are also large, but relatively finely divided.

Three tall groundsels or ragworts – Senecio spp. – are blooming the 3rd week of July 2022. They can grow to 3-5’ high and have compound flower heads. The heads are surrounded by a protective row of smooth, equally sized bracts often tipped with black, (and some very short bracts),

and a pinwheel of a few to several yellow ray flowers. The leaves are similar in size, ranging 3-5”, as they alternate up the stems. The leaf shapes are different and, therefore, are helpful in ID.

Saw-tooth Groundsel – Senecio serra – has oblong leaves with serrated (roughly toothed) leaves.

Arrowleaf Groundsel – Senecio triangularis – has stalked triangular and serrated leaves

and grows near streams and seeps. They can be a host plant for Fern-leaf Lousewort (see above).

Thick-leaved Groundsel – Senecio crassulus – is at high elevations. The slightly succulent, thickish oblong leaves are larger at the base and become smaller and often more clasping as they go up the stem. All is smooth. Flower heads typically have 8 ray flowers. Plants are often only about 2’ tall.

A bit lower in stature:

Cinquefoils are common in a range of habitats. They were addressed in an earlier “What’s in bloom”. However, we include them again here generally because they are so common.

Tall Cinquefoil – Potentilla arguta – is often seen arguing. The flower stalks stand stiffly up and the flowers are clustered, almost in each other’s faces.

The pale yellow to creamy yellow flowers are slightly larger than the very similar Sticky Cinquefoil – P. glandulosa whose flower clusters are more relaxed. Both species have sticky glands and pinnately divided large leaves. Without measurements, I find they can be very difficult to tell apart.

Other taxa include variants of P. gracilis, P. diversifolia, and P. ovina which are good botany puzzles.

Sticky Geranium – Geranium viscosissimum – is pervasive in many habitats from sage flats to meadows to forest openings.

In moister or higher, cooler sites it may be accompanied by the white Richardson’s Geranium – Geranium richardsonium.

Found mostly at higher elevations, Nuttall’s Linanthus – Leptosiphon nuttallii – looks a lot like its cousin Multiflora Phlox – Phlox multiflora – which may be blooming nearby. The tubular flowers with a flare at the top are similarly designed and fragrant. In both species, the leaves are opposite but Linanthus leaves are each divided into very narrow lobes that look frilly.

When in flower, both species look like remnant snow patches.

A side note: L. nuttallii used to be in the genus Linanthus, but the taxonomists determined that their pollen grains were distinct and so it belongs in the genus Leptosiphon).

Aster-like Plants

In the next month or so, we will be seeing many aster-like flowers, which are cousins or first-cousins-once-removed in the Aster or Composite Family. All are similar in having “heads” of many small flowers: ray flowers that range from white to blue to pink ring around the disc flowers in the center. With close examination of bracts, leaves, and later fruits, one can begin to tell them apart.

Fleabanes typically have a row (or two) of equally long narrow bracts that protect a head of many narrow ray flowers surrounding the disc flowers.

There are many species, but here are two larger, more obvious ones blooming in meadows right now

Aspen or Showy Fleabane – Erigeron speciosus – is truly showy with its many narrow (.5-1.5 mm) blue-to-violet ray flowers setting off the yellow centers of the composite head. Egg-shaped, blunt leaves with stiff-hairy margins alternate up the sturdy 1.5’ stems.

Wandering Fleabane – Erigeron peregrinus – has oblong leaves; wider (1.5-3 mm) and fewer ray flowers, and is found in moist places at high elevations

Several species of Beards-tongues – Penstemon spp. – are blooming all around, some only a few inches tall and others up to 2’+ high, and therefore must be mentioned here. The genus is pretty easy to determine with its opposite leaves and (usually blue) tubular flowers which have two lobes above, and 3 lobes below. There are technically 5 stamens (penta- five, stemon – stamen) but one stamen is sterile (staminoid) and usually hairy and lies at the base of the tube. The other 4 stamens typically coil up within the tube. One straight stigma (seen below between two anthers) is at the center of all.

There are several different species to decipher using clues of hairiness of leaves, stickiness of inflorescence, stickiness and shape of sepals, hairs on the back of anthers, and arrangement and size of anthers….. Truly puzzles for the hardy botanist. The flowers are hard to photograph for ID purposes so above is only one example — not sure of ID.

Penstemons are now in the Plantain or Plantanginaceae Family.

Two low white louseworts are intriguing to look at. I often get them confused at first.

Leafy Lousewort – Pedicularlis racemosa- has elongate, finely toothed leaves. The white flowers are held between two sepals. These flowers are blooming in forests right now.

Coiled or Beaked Lousewort – Pedicularlis contorta – has a coil-like flower similar to Leafy Lousewort but grows at higher more open elevations. Coiled Louseworts have more pinnately divided leaves and their bracts are also divided. They are starting to bloom in open high elevations such as just south of Teton Pass.

These coiled, “beaked” flowers have co-evolved for “buzz” pollination by bumblebees. The vibration of the bee’s wing muscles starts the pollen grains—tucked way back in the flower — bouncing their way up and out of the long coil to shake out upon the bee. The bee tries to glean the pollen off its hairy back to feed to its young, but can’t reach between its head and thorax. When the bee lands on a flower while the female stigma is protruding, the stigma twists and fits between the bee’s head and thorax reaching the remaining pollen and is pollinated.

Louseworts are now known to be hemi-parasites and have been moved from the Snapdragon to the Orobanche Family.

Silky Phacelia – Phacelia sericea – sends up spires of deep-violet flowers above several divided leaves. It is truly a higher elevation plant of the West, often growing above timberline in rocky soils. It is showing up on slopes south of Teton Pass.

A USDA Forest Service report says that a study found that in alluvial soils around gold mines, Silky Phacelias retained more gold in their tissues than other surrounding plants—miniscule pots of gold. A very odd fact. Actually the pots of gold (for insects) are the pollen grains on the tips of the many purple anthers shown below.

These are the typical flowers of our high meadows found in July in Teton County. Summer goes fast so please take the time to enjoy them.

Frances Clark, Wilson, WY

July 22, 2022

And please let us know of any corrections. We strive to be accurate.