Deciduous trees and shrubs lay bare their branches in winter. Loosing their leaves is a survival strategy to withstand cold and drought. It also prevents breakage of limbs from the weight of snow on broad surfaces. (Compare with the evergreen species in our previous posting.)

First, the basic design and function of a deciduous leaf.

As with needles of evergreens, deciduous leaves are essentially solar panels and food factories. Very simply put, through the process of photosynthesis, green chlorophyll with cloroplasts captures sunlight which powers leaf cells to combine water and carbon dioxide to make sugars and release oxygen.

Water with nutrients comes into the plant through fine roots by osmosis, travels up through a series of pipes – vessels – and out into the leaves. On the underside of the leaf are lip-like openings – stomates – which let in CO2. The cells in the leaf create sugar (energy) and release the by-product oxygen. Oxygen flows out the stomates into the air (which we breath) along with a lot of water vapor. At night when the stomates are closed and photosynthesis is shut off due to no light, additional processes occur that uses the sugar energy along with various nutrients to produce products for plant growth.

Broad leaves are very efficient factories. Their wide surface can gather lots of light; and as long as there is water and sufficient nutrients, particularly nitrogen, they have the resources to power and produce what the plant needs to grow in a short season. However, these chemical processes require a certain temperature range to be efficient and, as noted, plenty of water. Water transpiration helps to cool the machinery – so to speak – in the leaf during warm weather.

Winter poses a problem: At lower temperature the chemical processes don’t work. As the air freezes, water in leaf cells freezes and ruptures the cells. Then the groundwater freezes, the factories can’t get the basic raw materials of water and nutrients they need.

So, when the days get shorter and cooler, hormones start closing down the factories in a very orderly process. Any extra materials in the leaf like nitrogen are relayed back into the stem for storage; sugars and starches are stored in the parenchyma cells. The pipes out to the leaf become sealed off with cork; and the now-brown leaf drops off.

Other processes have occurred in the plant. After producing leaves and flowers in spring, by mid-summer the plant begins making fruits and forming buds. Buds contain the initial stem cells for growth the following spring. The stored sugars and starches provide energy to keep the bud cells alive. Stored energy is also used to keep alive the the thin ring of living cells found just under the bark of woody plants – the cambium.

Buds contain the initial stem cells for growth the following spring. Triggered by day-length and warmth, hormones will stimulate the relay of energy and materials to the buds so the stem cells can begin to build new food factories–leaves–in spring .

Other adaptations occur for winter dormancy so that plant cells can withstand below-freezing temperatures, but enough said for now.

ID of Winter Woody Plants:

Botanizing in winter can be fun and challenging. The obvious features for identification have shriveled so you need to use more detective work, gathering as many clues as possible. Take some photos, look closely at the entire plant and bark, and then if permitted take samples and bring them inside where it is warmer to handle and compare the specimens. Don’t forget to notice where it is growing–habitat. Once you have deduced a name, you can look up more info about the plant including what they looked like in summer!

Key features:

- Arrangement of buds – alternate or opposite

- Buds: # of scales, shape, surface texture

- Leaf scars and traces

- Bark

- Habit e.g. shape

- Smell and taste

More about buds:

Buds protect the growing tissue (stem cells) of a new stem or flower that will emerge in spring.

Some buds have distinctive shapes and sizes. Bud scales cover the stem-cells in definite patterns depending on the species. Buds can be smooth, hairy, sticky.

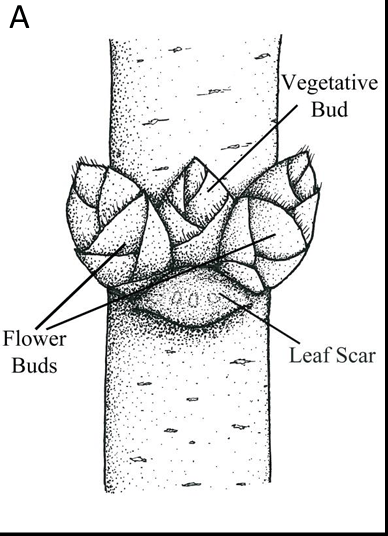

Buds sit at the juncture of twig and leaf e.g. in the “axils” of each leaf. In winter you can see the leaf scar—where the leaf fell off leaving “traces” where the veins/vessels carried water and nutrients into the living leaves.

The shape and size of the scar and the number and arrangement of leaf traces are clues to ID.

Often you will see a difference in bud size and/or shape on the same plant. It is often the difference between a flower bud and a new stem which will have leaves.

Woody Plant ID:

The 5 species below have early wind-pollinated flowers that produce small dry fruits that are well dispersed before winter.

Trembling Aspen – Populus tremuloides – is our most common deciduous tree in Jackson Hole. Aspens form clones that blanket large areas of hillsides, particularly on the eastern hills of the valley.

In spring the spade-shaped leaves unfurl a luminescent green and by October fall off in a dramatic show of yellows and oranges. In winter the smooth, greenish-white bark stands out. By looking closely at the shape and patterns on the trunks, one can see the similarity among these genetically identical sprouts.

The whitish trunks with black scars where the limbs branch out are the easiest ID feature. The bark is usually smooth and the outer cells of the bark will often rub off on your hand. There is a layer of green chlorophyll just under the thin bark which aids in photosynthesis in winter.

The buds are smooth, dark brown, elongate, with a few bud scales and a leaf scar with 3 traces.

Aspen have cousins called Cottonwoods. Narrow-leaf Cottonwood – Populus angustifolia, (and P. balsamifera, P. acuminata) – are easiest to tell apart from Aspens by the plant’s larger size overall and much thicker, rougher bark. Cottonwoods grow in floodplains and along old drainage ditches.

They tend to grow as stand-alone trees or groups, not in clones. The lower trunks often have shaggy-looking side branches.

Cottonwood buds are larger than Aspens, and some are rather resinous and fragrant. Scales are less distinct.

Willows – Salix spp. – are in the same family as aspens and cottonwoods. We have 28 native species of willows in Teton County growing from alpine zones to wetlands and floodplains as shrubs. Several of our medium-sized species have stem colors ranging from yellow, orange, to reddish.

The easiest way to know a willow in winter is to look at the buds.

Buds alternate and have a single scale—sock like—over the growth point beneath. The bud scar is narrow with three bundle traces. Relatively larger buds on a stem harbor pussies – the silvery “furry” catkins that emerge in spring.

Thin-leaf Alders – Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia/occidentalis – grow in wet areas and are often inaccessible for a close look.

However you can often see the elongated buds dangling from 10-15′ high branches. These male catkins will open to shed pollen upon the wind in early spring.

The woody cone-like structures are last year’s female catkins that shed their seeds last fall.

Buds for next spring’s leafy stems have two opposite – valvate – scales on a bit of a stalk.

The bark is gray with lenticels – pores that allow for gas exhange through the bark of the stem.

Alders are important for preventing erosion along streams and avalanche slopes. Plants are able to establish in poor soils as they can fix-nitrogen with the aid of bacteria in root nodules. The nitrogen is used for the alder to grow. When the leaves drop and breakdown, the nitrogen is then available for other plants to use as well. The many fine alder roots also hold the ground.

Trees and Shrubs with large fruits—if you can find them:

Many of the following shrubs and small trees provide substantial fruits for a variety of birds, small mammals and large, and they tend to disappear fast, before winter. Branches and buds serve as nutritious browse for deer, moose, and grouse. Thickets provide protection from predators and wind. Bark and buds, and maybe a shriveled leaf or fruit, can help ID. Use all the clues you can find.

Douglas Hawthorn – Crataegus douglasii – are typically small 15-20’ roundish trees.

They have 1”, slightly curved to straight thorns. Thorns are technically modified stems. The young twigs are shiny maroon, aging to orange. The buds are distinctly round.

There may be a few remaining shriveled fruits, but the bears tend to get to them first. Hawthorns are frequent around LSR visitor center and along the Moose-Wilson Road. Watch for the thorns when you are out skiing.

Chokecherry – Prunus virginiana – can grow to 20′ or more. It is found along roadsides of Moose-Wilson Road, along Old Pass Road, up draws of buttes, and mixed into edges of forests.

Bark often has dots or lenticels—pores where gases can go in and out of the stem.

If broken and warm enough, twigs have an odd smell – a bit like almonds. Cherries have the chemical ingredients for cyanide.

Buds are alternate, pointed, with several smooth scales.

The leaf scar is roundish and with three bundle traces – the central one is larger.

Sometimes you are lucky to find an old leaf hanging on….This is very helpful! The leaves are 2-3” long, oblong with little teeth all along the margin.

You may also find an old fruit stem…it arches and sometimes has little stubs where the fruits were held.

The fruits were likely consumed by birds or bears. The hard seeds (pits) pass right through them. However, as humans it is best not to bite into the seeds…. they harbor prussic acid e.g. cyanide. Native Americans and fur trappers used to make pemmican from mashing the fruits and seeds in with animal fats for their own survival during winter. The process breaks down the pit poisons.

Serviceberry – Amelanchier alnifolia – is similar in size and habitat to Chokecherry. Look closely for the differences:

Bark is light gray.

Buds are pointed with several tidy scales, often pubescent. Leaf scars are very narrow.

Dried leaves are roundish with teeth near the tips.

Shriveled fruits are held on stems of various lengths..

Note: Unlike the Chokecherry’s fruit which is smooth, the shriveled serviceberry fruit has a rough spot at its end:

Seeing the differences Serviceberry vs. Chokecherry is not easy:

The stems of Wood’s and Nootka Roses – Rosa woodsii and R. nutkana – are covered with “prickles”, which arise from tissue layers on the stem. In winter, young stems are red to purplish and the prickles stand out. Older stems are gray.

Fruits of roses often remain throughout winter until wildlife are really hungry. If you dissect a rose hip you will discover the true fruits inside: several dry achenes each wrapping a single small seed.

The red hip is actually the swollen bases of petals and sepals fused together in a structure called a hypanthium. It has high levels of pectin and Vitamin C.

Snowberries – Symphoricarpos albus and S. oreophilus – still may hold onto a few shriveled white fruits.

The overall look is “twiggy” with slender side stems and small opposite buds.

Look at the thin, opposite branches with opposite small buds and the line between them.

The white mushy fruits are technically drupes, which have an outer skin, fleshy innards, and then a two very tough oval seeds. Critters from birds to small mammals appreciate the fruits and the protective thickets. Snowberry is also a key host plant for Vashti Sphinx Moths.

Red-stemmed Dogwood – Cornus stolonifera – is true to its name. Overall appearance of the plant is deep maroon.

Young stems are particularly red.

Buds have a single scale, like a willow; but notably the buds of dogwoods are opposite on the branch. The leaf scars are very narrow.

You may also find remnants of the array of fruits.

As they are energy packed with lipids, most of the white-to-blue fruits were quickly consumed by migrating birds in the fall.

Red-stemmed dogwoods are considered “moose ice cream.” The stems are favored by these huge ungulates. As the plants grow fast, I welcome the moose pruning my ornamental native dogwoods.

Silverberries – Eleagnus commutata – are most often found here in flood plains. You can see them spreading by rhizomes under cottonwoods along the Snake River. The silvery leaves alternate on the stems, often remaining into winter. Note the copper-colored, scaly texture of the stems and the simple buds.

The silvery oblong fruits dangle off 6-10′ high branches.

Research indicates that moose particularly like this plant for browse. Various birds will use the fruits. Domestic stock do not like to eat Silverberries.

Its relative, Russet Buffaloberry – Sheperdia canadensis – also has the little rusty dots on the stems indicative of the Oleaster or Eleagnaceae Family.

Note the buds are opposite. The terminal buds already have the formation of paired leaves in prayer. The oblong side buds have one scale and will emerge as leaf-bearing branches. The clustered round side buds will become small yellow flowers in spring: male flowers on one plant, female flowers on another plant.

The berries are red with the same rusty covering. I haven’t seen any at this time of year.

A few low shrubs with small dried fruits:

Sometimes you will see the fine 2’ tall stems and 3-4”-wide dried inflorescence of Birch-leaf Spiraea – Spiraea betulifolia var. lucidula – along a trail.

The flat-topped clusters of tiny flowers have become sprays of 5-parted tiny dried fruits that split open to release tiny seeds. These dried “corymbs” also hold snow.

Rubber Rabbitbrushes – Ericameria nauseosa var. graveolens – are abundant along the Game Creek Trail. This is just one of three look-alike sub-species in Teton County.

This species is a large, 2-4’-tall and -wide shrub.

with greyish, finely matted hairs on the greenish stem. The remaining leaves are very narrow, 2-3” long with 1-3 faint veins.

At the tops of the branches are clusters of hay-colored dried bracts remaining from the yellow composite flowers of the fall. They may still hold a few seeds attached to fluff – a pappus, but most have already flown off in the wind. It is in the Aster Family.

Break a stem and take a sniff. If warm enough, it yields a distinctive odor and an unpleasant taste—hence the species name “nauseosus” — a key way to know it is a Rabbitbrush. In warmer weather younger stems are flexible, rubbery, and produce a rubber-like sap which was of interest as a rubber substitute during World War II. The resins are of continued commercial interest. Click here for more detail. Hence the name Rubber Rabbitbrush.

It has two very similar cousins – subspecies – but just knowing this is a Rubber Rabbitbrush is an accomplishment

Another related and confused group are Sticky Rabbitbrushes – Chrysothamnus viscidifolius. They are usually only 1-1.5′ tall (more readily covered by snow),

Sticky Rabbitbrushes have twisted leaves and usually smooth brittle stems.

The plants are slightly sticky – viscid – in warm weather–hence the name. Both types of rabbitbrushes overall tend to grow in sunny dry, infertile, often disturbed soils.

Thats a lot of species! Take your time. See how many you can find. Enjoy!

Here is a summary:

Trembling Aspen – tree with white, thin bark with black streaks above side branches; clonal growth over hills,

Cottonwoods – large individual trees with thick ridged bark, in floodplains

Willows – shrubs often with colorful stems; buds with single scale.

Alder – up to 10-25′ colonizing shrubs along wetlands, light brown elongate catkins dangling. Gray bark with lenticels. Buds with two scales.

Douglas Hawthorn – 20′ rounded tree with 1″ thorns, round buds on reddish twigs.

Serviceberry – 20′ lanky shrubs with gray smooth bark; often pubescent buds with a few to several scales, narrow leaf scar; left-over fruits with rough at ends, contain several small seeds

Chokecherry – 20′ lanky shrub with dark bark with dots of lenticels; buds with several smooth scales, rounded leaf scar with one obvious trace; round fruit held on on curved stalks, smooth at end. Hard pit in center. Distinct smell to broken twigs

Rose, Woods or Nootka – 3-5′ shrubs; prickles on stem: young stems reddish, old grey; red rose hips often remain on plants into spring.

Snowberry – common shrubs 2-4′ tall in a variety of upland habitats – very “twiggy” with thin opposite branches and buds; fleshy fruits white and often shriveled or gone.

Red-stemmed Dogwood – shrubs to 4-6’+ high and wide with distinct maroon-to-red stems. Branches opposite; buds narrow bud with single scales. Usually wet areas, often with willows.

Silverberry – rhizomatous 4-6′ upright shrubs, found in floodplains; silvery oval fruits hang off of of rusty looking stems, silvery leaves may remain, alternating leaves and buds.

Buffaloberry – 3-4′ shrubs, rusty stems with opposite branches and buds, terminal buds like two leaves in prayer, clusters of round buds on the side to become flowers. Here and there in shade.

Birch-leaf Spiraea – 2-4′ stems very thin, has flat-topped dark brown clusters of tiny dry fruits. Woodland trails.

Rubber Rabbitbrush – usually greenish stems covered in fine white hairs – tomentum; alternate leaves linear, straight, 2-3″ long; stems have strong odor (if warmed) and flavor; bracts from yellow flowers remain through winter. Dry open sites, often with sagebrush.

Sticky Rabbitbrush – only 1-2′ tall, browned leaves alternate, twisted. Bracts remain on top. Dry sites.

______________________

Dec 1, 2024, (minor corrections 12.12.24)

Frances Clark, Wilson, WY

As always we appreciate your comments and corrections. Please email tetonplants@tetonplants.com

Note: Plants are highly variable in their size and range in habitat. Heights are estimated for this area and habitat based on personal observation.