This spring was moist and relatively warm so the flowers flourished and pollinators were abundant. Thus many, many of the flowers were pollinated by bees, flies, wasps, butterflies, moths, and more, thereby, setting the stage for developing fruit.

Fruits envelop seeds and serve to spread the seeds out into the world away from their parents. Fleshy fruits have evolved to be eaten by mammals and birds and then be excreted or regurgitated away from the parent plants. The flesh carries different kinds and levels of nutrients from starches and sugars to energy-packed lipids. The coverings are in different colors, often red, but also white, blue, black, and orange. The seeds within may be abundant to just one, but all count on wildlife to transport them elsewhere.

First, some basic botany (feel free to skip):

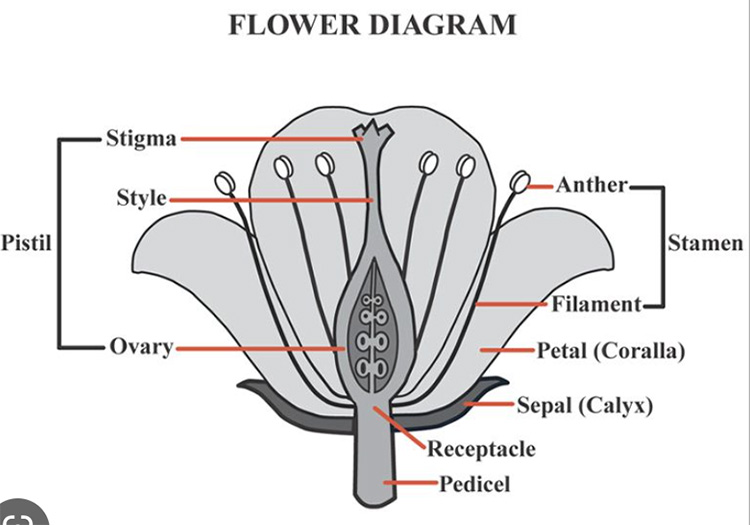

The anther, e.g. the top part of a stamen, produces male pollen grains; the stigma, the top part of the pistil, is where the pollen lands, and if compatible, grows a tube down through the style into the ovule with an egg, where it releases two sperm, one to fertilizes the egg inside the ovule, the other to form food/endosperm (a process called double fertilization). Thus a seed is formed. (Flower diagram from Pinterest:)

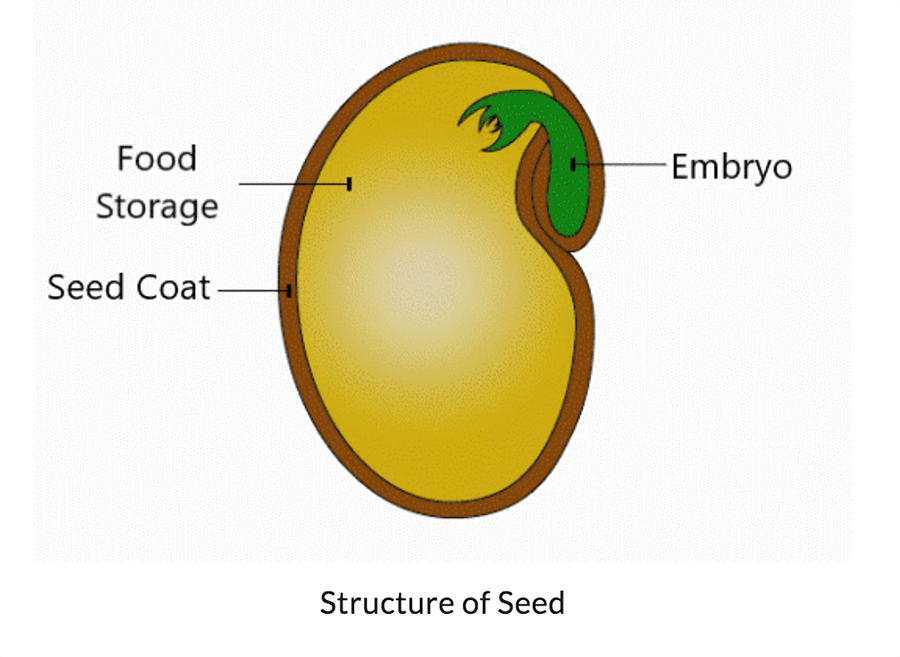

A typical seed includes a tiny plant (embryo), extra food (endosperm), and a protective seed coat. (Illus: courtesy of edurev)

These seeds in turn are enclosed inside a fruit which develops from the ovary (sometimes called a carpel). Ovules become seeds, Ovaries/carpels become fruits.

Fruits come in all sorts of shapes, sizes, structures, smells, tastes. Fruits are key to seed dispersal. This posting highlights some of the fleshy fruits you can see around the valley right now. Enjoy looking for the variations.

Lush Berries (loosely defined) – attract birds and mammals to disperse seeds

Several early blooming shrubs produced fruits that have already been scarfed up by birds and others. For instance, it is hard to find the pairs of red fruits of Utah Honeysuckle – Lonicera utahensis – and the twin black fruits held in maroon bracts of its relative Twinberry – Lonicera involucrata. Favored huckleberries – Vaccininium membraceum, V. scoparium – were in short supply or already consumed. However, other fruits are at peak and abundant.

Many wild fleshy fruits are in the Rose Family. They are related to the apples, cherries, plums pears, and peaches which we love.

Serviceberries – Amelanchier alnifolia,

and Chokecherries – Prunus virginiana – dangle their fruits.

Black Hawthorns – Crataegus douglasii – are especially abundant right now along Moose-Wilson Road and around the Lawrence Rockefeller Preserve visitor center.

The orange fruits of Mountain Ash – Sorbus scoparia – stand out above the alternating compound leaves of the 6-10′ or more shrubs.

Birds, bears, coyote, fox, and others like all these juicy fruits and deposit the seeds.

Thimbleberry – Rubus parviflora – is also in the Rose Family. These 3-4’ shrubs are found along streams or moist sites that provide enough water for the 4-6″ leaves to stay turgid. The raspberry-like fruits go fast.

And there are also rose hips forming on Wood’s and Nootka Roses – Rosa woodsii, R. nutkatensis. These leathery structures are held out on prickly stems and compound leaves typical of any rose.

Tough rose hips are usually not the preferred food at this time of year–they become important later on in winter when other food sources are more scarce. A variety of our local animals eat the fruit: mule deer, moose, and elk, bears, coyotes, and rodents, as well as some birds such as American Robins and grouse. Rose hips are high in a variety of vitamins, particularly vitamin C, as well as minerals and antioxidants. Hips have been used for making tea to ward off colds and flu.

Other Shrubs with fleshy fruits visible along shady trails:

Russet Buffaloberries – Shepherdia canadensis – form bright red fruits on 3-10’ shrubs.

Last spring, male and female flowers bloomed on separate plants as a strategy to prevent self-fertilization. Male flowers as shown below have only stamens. The glistening, sugary, donut-like nectary at the base of the stamens attracted pollinators to pick up pollen and then fly it to another Buffaloberry plant with female flowers, also with appealing nectaries.

Only the female flowers, of course, produce fruits.

Black and grizzly bears, as well as grouse, all eat the berries. The plants can grow in relatively poor soils because they are nitrogen fixers. By adding nitrogen back into the soil, plants also provide islands of nutrients for other colonizing plants.

Red-stemmed Dogwood – Cornus racemosa – produce bunches of elegant white berries.

Note the distinctive opposite, oval leaves with parallel veins.

Dogwood fruits are important as they are high in lipids which have extra energy needed for migrating birds. Whole plants are especially relished by moose!

Another plant with opposite leaves and white berries, but not at all related, is Snowberry – Symphoricarpos spp. Due to unappealing toxins, fruits tend to hang on a bit longer into winter when the toxins are broken down in the cold. Ruffed and Dusky Grouse, along with other birds, consume them.

Throughout the year, these twiggy shrubs provide important wildlife cover .

The creeping evergreen Oregon Grape – Mahonia/Berberis repens – sports bunches of blue , one-seeded berries. If you gently scrape the roots, you can see a yellow color. The plants, including fruits, contain berberine, a chemical that has been used for centuries and is being researched as a potential for use of diabetes, heart disorders, and as an antioxidant. As always, know your plant and check the medical literature before using or consuming any native plant.

Wildflower berries can be seen in moist or shady spaces:

Red Baneberries – Actea rubra var. rubra – literally stand out above a 2-3’ cluster of compound, toothed leaves. There is also a variety – var. neglecta – with white berries.

Do not eat! “Bane” means watch out/poison, which they are. The berries also taste terrible to us but not to the birds that eat them. They gobble up the fruits, fly off, and poop out the seeds. This plant is in the highly variable, mostly poisonous Buttercup Family – Ranunculaceae.

Twisted stalk – Streptopus amplexifolius – grows 3-5’ tall most often along streams. Look under the arching stems

for red ovoid fruits dangling from kinked stalks.

The fruits come after the delicate yellow flowers with 6 curled back tepals have been polllintated.

Fairybells – Prosartes trachycarpa – has lumpy, thumbnail-size fruits with an orange-then-red, velvet-like covering. These fruits are usually held in pairs on the tip the 2-3’ stalks.

False Solomon’s Seals – Maianthemum spp. – have fruits borne at the ends of arching stems with alternating leaves and parallel veins. Starry False Solomon’s Seal – M. stellatum – tends to be a smaller, more upright plant and fruits ripen sooner than it’s larger relative. It is interesting to watch the progression of fruit color: berries start off with a distinct stripe,

which slowly expands with a reddish wash,

and then the fruits become black.

False Solomon’s Seal – M. racemosum – is a larger, 1-2′ arching plant with a more branched inflorescence.

The spotted fruits eventually turn red:

Both these species have rhizomes that can be divided for home gardens.

Look for these and other fleshy fruits on your hikes. Make it a treasure hunt and enjoy the differences in color, consistency, seeds, and even in taste–a tongue tip (but not baneberry!).

And look for what may be consuming them…

There are many other fruits out there…see What’s in Fruit? – Part II: Dried Fruits in the next posting.

Frances Clark, September 1, 2025

As always, your comments and corrections are most welcome! Send to our email – tetonplants@gmail.com — we will respond when we aren’t out botanizing.