Not all fruits are brightly colored and juicy. (see “What’s in Fruit? – Late Summer 2025 – Part 1: Fleshy Fruits”). Seeds have different strategies for dispersal: Flying off on the wind, hitching a ride on fur and clothing, using gravity to settle down, and/or being ejected away from their parent plant. Luck is an essential component of seed dispersal and success.

Here are some examples of dispersal strategies. Enjoy looking at the details of how plants work.

Fruits that Stick:

Some fruits have little hooks like velcro – the notorious invasive Houndstongue – Cynoglossum officinale – is one such species.

Yet, another is the pesky native appropriately called Jessica Stickseed – Hackelia micrantha.

Sweet Cicely – Osmorhiza chiliensis – fruits are called schizocarps e.g. split fruits. This is typical of the Parsley Family. In this woodland species, fruits are sharply pointed and have stiff hairs to stab and grab you.

Fly on Wings:

Related to Sweet Cicely above, is the very large Cow Parsnip – Heracleum spondylium. It too has schizocarps held out in umbels – umbrella like structures. However, its schizocarps are flat and very thin so they skim off on the wind.

Upon a close look you can see how the two sides of the schizocarp are held together by a delicate filament. It is surprising how long these fruits will hang out there amidst the breezes. Also, note the darker seed inside inside each half. And to the upper right, you can see the left-over filaments–so very delicate looking, but sturdy.

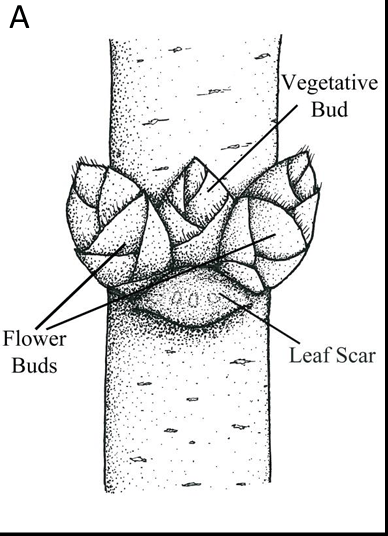

Rocky Mountain Maples – Acer glabrum – have structures called samaras. The male flowers (below) are borne on separate tall shrubs (usually)

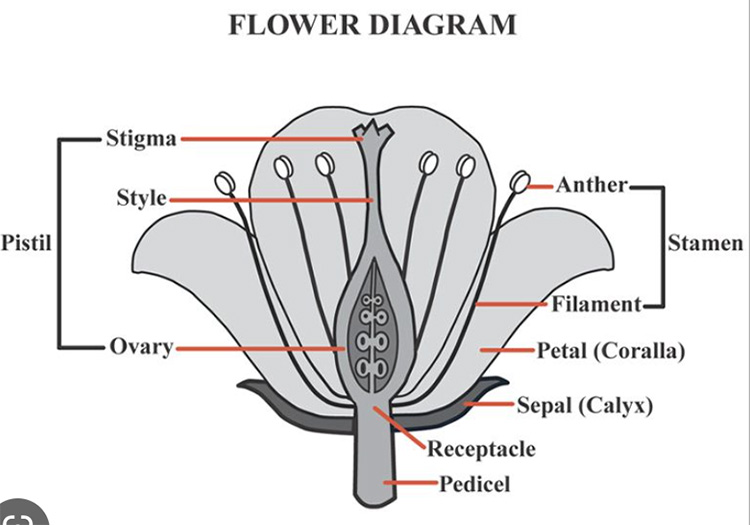

from those with female flowers. Below you can see the two-parted stigma of the female flower ready to receive pollen.

After the ovules are fertilized, the samara develops with two enclosed seeds, each with a wing derived from the ovary.

As children we used to watch the dried fruits break away from their branches and helicopter down to earth. Various birds particularly white-crowned sparrows and finches are known to eat the samaras, and moose, elk, mule deer browse heavily on maple shrubs.

In the Legume or Pea Family, Western Sweetvetch – Hedysarum occidentale – has flattened pods with segments called loments. When the loments dry, the segments break apart and are free to fly – like frisbees on the wind. You can see the silhouettes of the bean-shaped seeds within sections of the loment fruit.

Fly on Fluff

Spires of fireweed are spectacular at this time of year with their long seed pods splitting, curling, and releasing 100s of seeds upon the breeze. Each seed has a bit of fluff – non-technical term – at the tip.

You may perhaps come across the twining Western Blue Virgin’s Bower – Clematis occidentalis. Growing primarily in the shade, it is a woody vine with 3-parted leaves.

The individual fruits are derived from individual pistils/carpels typical of the Buttercup Family. Fruits – technically achenes – have one seed inside and are covered in long hairs. The wind will help pry the seeds form the tangle and fly off free.

The Aster Family, covered in the last “What’s in bloom – mid August 2025”, produces fruits termed cypselas (vs. achenes) that are formed from the inferior ovary of each tiny flower. Each flower produces only one seed. Many have a pappus of fine hairs (e.g. fluff) that carries the fruits off on the wind.

Hairy False Golden Aster – Heterotheca villosa – has hairy cypselas each with a pappus of fine hairs at the top. Note there are many fruits on the platform, typical of the Aster/Composite Family.

Dandelions, asters, goldenrods, rabbitbrushes and many more have this method of dispersal, including the highly invasive Musk Thistle – Carduus nutans.

Habitat Heroes, trained and organized by the Teton County Weed and Pest – Meta Dittmer – and TC Conservation District – Morgan Graham, have in deed done heroic work clearing out thistles up Game Creek and other areas around the valley. More volunteers welcome! Contact Meta Dittmer.

Growing amidst mountain sagebrush and rabbitbushes in dry habitats, 1-2′ shrubs of Spineless Horsebrush – Tetradymia canescens – stand out at this time of year. They have silvery pubescent stems and leaves topped by plumose heads of

cypselas covered in fine long hairs. These fruits are dispersed on the wind.

It is fun to pull out the handlens and see the variation in the cypselas: look at the pappus and other coverings of the fruits of the Aster Family. These details help taxonomists determine the different species of this world-wide family–the largest plant family on Earth except perhaps the Orchid Family.

Birds and Gravity – (pluck and drop)

Other composite fruits have scale-like projections at the top of each cypsela. Its not clear whether this helps the cypsela hitchhike on passers-by or perhaps to deter marauders from getting to the tender fruits below. Five-nerved Little-sunflowers – Helianthella quinquenerva – is an interesting example.

The cypselas are dark with a bit of a brush at the tips (technically a pappus of the non-fluff style). The lighter, flimsier, scale-like structures surrounding them are technically called paleae (palea singular), and are not part of the fruit itself. In this case, the paleae likely serve as barricades to insects wanting to eat the nutritious seeds.

Other cypselas nestle deep inside stiff, sharp paleae as seen in Arrowleaf Balsamroots – Balsamorhiza sagittata. Look closely in the center and you will see the squarish-shaped tops of the cypselas. The sharp dividers are the paleae.

Being able to separate the fruits from the paleae is helpful when collecting seeds for restoration projects, as do the Grand Teton National Park volunteers. These Seed Heroes, led by Jasmine Cutter, have been harvesting these and other seed this summer for habitat restoration. If you wish to volunteer, contact Jasmine Cutter:

These types of fruits are often plucked out by birds, shaken out by wind, or just dropped when the heads fall apart.

Fruits of Western or Rayless Coneflower – Rudbeckia occidentale – sit up on the cone-like central platform – receptacle – and are distributed by birds and gravity. Interestingly, it appears that the short, tough, paleae hold the fruits in place.

Shake Outs:

Some dried fruits split open and shake out the seeds, often over time. Landing at different intervals helps increase chances of success, depending on the seed’s germination needs regarding moisture and timing.

Look for Lewis’ flax – Linum lewisii – where the capsules split apart.

Monkshood – Aconitum columbianum – have smooth follicles that gradually split open and shake out tiny rough seeds.

They look very similar to the fruits their relative Tall Delphinium/Larkspur – Delphinium occidentale – except Monkshood fruits are smooth on hairy stems. Larkspur fruits are finely hairy,

and the stems are smooth with a bluish-gray covering that can be rubbed off (glaucous) and the lobed leaves are stalked.

Also in the Buttercup Family, Colorado Columbine – Aquilegia coerulea – have three-parted dry fruits with seeds inside.

The mouth-like dried fruits of Louseworts – Pedicularis spp. – release seeds a few at a time. Below is Large Lousewort – P. procera – seen around Wally’s World and Game Creek. Look for other Lousewort fruits, as well.

Leopard Lily – Fritillaria atropurpurea – are clearly seed shakers.

Below is the globe-like, dry fruit of non-native White Campion – Silene latifolia. White Campions have separate male and female plants.

The dried petals and firm ovary form an elegant cup

that shakes out seeds.

As these plants are primarily annuals, they depend on these seeds for their future.

You can see the resemblance to its much smaller native relative Ballhead Sandwort – Eremogone congesta, also in the Pink or Caryophyllaceae Family. Both flowers and fruits provide details of family connections.

A couple more to look for:

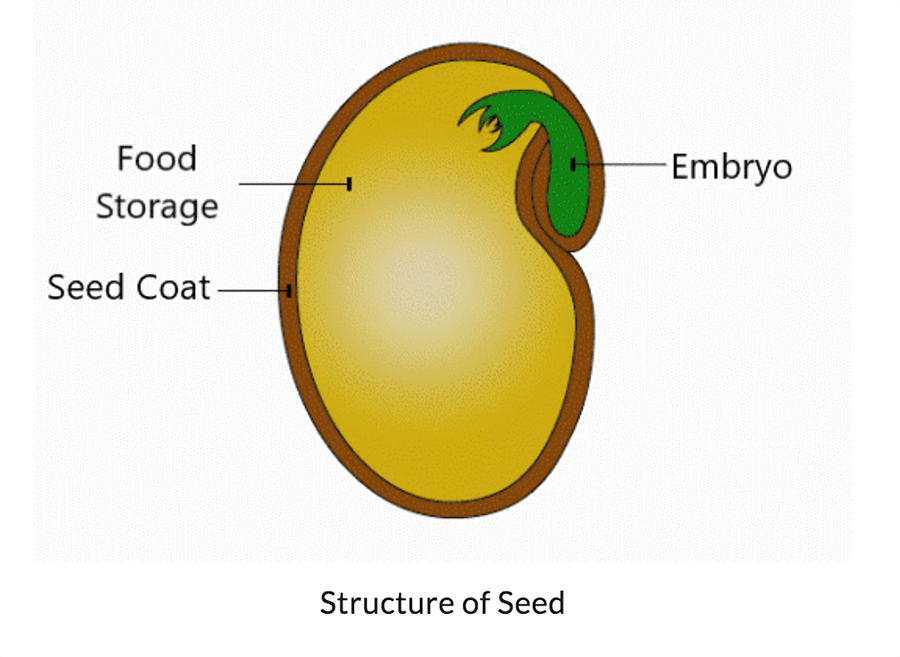

Orchids, such as this Coralroot – Corallorhiza spp. – have dust like seeds easily scattered by the lightest breeze.

Orchid seeds rely on mycorrhizal fungi to nurture the the embryo. As this genus does not have chlorophyll, it also depends on different mycorrhizae to support adult plants.

Dried fruits of Pinedrops – Pterospora andromedea – slowly break apart and release

spectacular seeds – if you can see them. Each tiny seed is attached to a membranous wing to aid their flight to new ground. A 10x handlens reveals their delicate nature better than a camera.

As these 3-4′ plants have no chlorophyll they rely on mycorrhizal fungi to relay nutrients from various coniferous host plants.

Fruits that Fling:

Sticky geranium – Geranium viscossissimum – flowers each produce a total 5 or more seeds, usually 1-2 nestled in each of 5 separate compartments of the ovary at the base of the pistil. When the ovary begins to dry, tension builds up, the style splits apart, curls, and literally catapults the seeds several feet beyond.

Our native lupines – Lupinus spp. – are in the Pea or Legume Family/Fabaceae. As with our edible peas and beans, lupines have pods with several individual seeds inside. In lupines, these pods dry, twist, split, and eject the hard seeds beyond the parent plant. Do not eat the seeds. Our species of lupine are poisonous – including its foliage and even more so the seeds.

Over the next few weeks, see how many different fruits you can find, and try to figure the modes of seed dispersal.

Botanizing is fun in fall.

Frances Clark, September 1, 2025

As always, comments and corrections are most welcome.